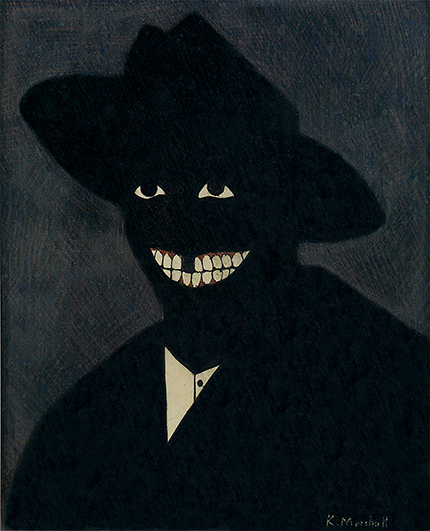

Kerry James Marshall

“I used the power of abstraction to solve [the] deficiencies in the way the figure was represented. I wanted to use all of the color complexity that I’d learned but to keep it close to black history, culture, and subjectivity.”–Kerry James Marshall

Words by Kerry James Marshall

In the late 1960s, early 1970s, maybe it happened a little earlier, there seemed to be all these conversations about participation in the mainstream and how to go about achieving it. For a lot of artists, it seemed that the only way to do this was to abandon the black figure. Not only was abstraction supposed to be more advanced, but also you were never going to achieve any great recognition until you let go of the black figure. And some people thought that the reason [Charles] White never got the kind of recognition that people thought he deserved was primarily because he was too close to those black figures. There was a period in which I abandoned the black figure too, because I wanted to spend more time figuring out what pictures looked like, and how surface, color texture, and all those things operated. I was doing a lot of collage work and mixed-media stuff. The Ellison book [Invisible Man] became the trigger that sent me back to the figure.

I understood on some level that the abandonment of the black figure was a kind of loss and that I’d surrendered to a power structure rather than trying to challenge and overcome it in some way. And so A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self became an instrument to solve what I thought might be some deficiencies in some of the work that White was doing, as well as the work that some other black painters were doing in their use of the figure; I used the power of abstraction to solve these deficiencies in the way the figure was represented. I wanted to use all of the color complexity that I’d learned from [Sam] Clayberger, but to keep it close to black history, culture and the subjectivity of White’s work. So A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self was a way of starting at a zero degree because it was flat, it was schematic, but it was built on all of the stuff I’d learned about picture making from my teachers at Otis [College of Art and Design] that was opposite to the way a number of black artists approached the picture; the only way they could stay with the black figure was by compromising it, by either fragmenting it, or otherwise distorting it, by making it green, blue or yellow, or some other way to deflect the idea of its blackness.